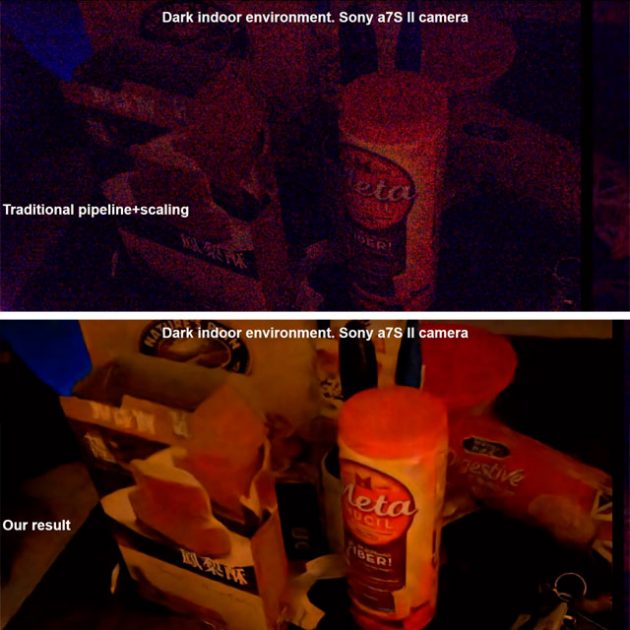

At this year’s IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), a group of researchers from UIUC and Intel Labs showed off how learning-based artificial intelligence can help imaging in low light. It is almost surreal to see how an otherwise darkened photo can be made bright as day. It was that crazy. Here, have look at the result:

The demonstrations not only show us how learning-based AI for processing can make low-light image significantly brighter but also offering more accurate colors over the current enhancement methods. Here’s the abstract of this breakthrough innovation:

“Imaging in low light is challenging due to low photon count and low SNR. Short-exposure images suffer from noise, while long exposure can lead to blurry images and is often impractical. A variety of denoising, deblurring, and enhancement techniques have been proposed, but their effectiveness is limited in extreme conditions, such as video-rate imaging at night. To support the development of learning-based pipelines for low-light image processing, we introduce a dataset of raw short-exposure night-time images, with corresponding long-exposure reference images. Using the presented dataset, we develop a pipeline for processing low-light images, based on end-to-end training of a fully-convolutional network. The network operates directly on raw sensor data and replaces much of the traditional image processing pipeline, which tends to perform poorly on such data. We report promising results on the new dataset, analyze factors that affect performance, and highlight opportunities for future work.”

While exciting, don’t expect this new method to land on your smartphone’s cameras anytime soon. For starter, it does require RAW images for training which means most images captured by today’s smartphones will not make the cut. But it is a start of something really, really exciting. If materialized and eventually applied to consumer-grade imaging devices, such as smartphones, it will, for once, enable imaging devices to actually ‘see’ better than human eyes.

When I said ‘see better’, I do not mean imaging devices aided by thermal or IR technologies. Surely those does not qualify as “seeing better” because they are virtually void of accurate colors, much less accurate hues. If you are keen, you can read up on the paper HERE, or just be awed by the process in the video embedded below.

Images: YouTube.

Source: Geekologie.